Welcome back for the second part of my own little piece of self-reflection here. This is my list of the top 25 films I saw for the first time in 2012:

25. Les Diaboliques - (1955, Dir. Henri-Georges Clouzot)

A fantastic deconstruction of thriller conventions, before a lot of them even came to exist. It is not the emergence of a body that sets the wheels in motion, but the disappearance of one. The determined and intelligent detective is an uncomfortable figure of pressure. Then of course, there is the climax, an ultimate image of pure horror. Les Diaboliques is sheer brilliance.

It isn't until the final moments of Arnold's low-key Science Fiction film based on the novel by I am Legend author Richard Matheson that it emerges as a distinct genre classic. After being hit by a toxic gas (back in the time when it was something as simple as 'Science!') Scott Carey finds himself shrinking until he is only a few inches high. Queue the iconic and exhilarating fight with a house hold spider with genuinely good effects! But it is the surprisingly metaphysical ending, where a now microscopic Carey imagines himself as part of an infinite number of universal loops that will leave you questioning the fragility of our placement here on earth.

David Thewlis gives an amazingly fierce performance as intelligent misanthropic drifter Jonny, in Mike Leigh's nihilistic odyssey. A dark look at the human race through the eyes of someone so brilliantly beyond help from anyone who tries to reach out to him. Leigh's script is full of black comedy and social satire, including the famous doomsday rant that might just be my favourite speech of the year, you can watch it here.

David Thewlis gives an amazingly fierce performance as intelligent misanthropic drifter Jonny, in Mike Leigh's nihilistic odyssey. A dark look at the human race through the eyes of someone so brilliantly beyond help from anyone who tries to reach out to him. Leigh's script is full of black comedy and social satire, including the famous doomsday rant that might just be my favourite speech of the year, you can watch it here.22. The Man With a Movie Camera - (1929, Dir. Dziga Vertov)

Off the back of this years Sight and Sound poll I looked up Vertov's experimental montage piece. A truly landmark testament to civilization. An explosion of images and editing, it becomes a symphony of light, sound and texture. Our camera man is separated from this existence, he cannot experience it's joys but it is his duty to capture the wonders of it. What keeps this film from being a mere museum piece, such as The Battleship Potemkin, is the cheeky tone and incredible, frequently dangerous stunts.

21.Anatomy of a Murder - (1959, Dir. Otto Preminger)

Such a fascinating depiction of a murder trial. This isn't merely a case of getting the good guy off, in fact we are never quite sure of Manion's true composure at the time of the shooting. It isn't the point, this is a study of murder as a legal matter. Jimmy Stewart's small town retired attorney facing off against state lawyers is projected by a sizzling script with an abrupt frankness and sharp humor that remains completely riveting for it's entire 160 minute running time.

20. The Sacrifice - (1986, Dir. Andrei Tarkovsky)

Tarkovsky's final film is a plea to mankind. For humanity to survive one must be prepared to sacrifice. At the outbreak of World War Three Alexander promises to God that he will give everything; his family, his house and even his sanity in order for the world to be spared. Shot on Faro Island, the film is an homage to Bergman, Tarkovsky even used Nykvist, Bergman's cinematographer, to shoot the film full of natural light and medium tones. The film is wrought with direct urgency that comes come Tarkovsky being just months from death. The climax is the most tragically beautiful image of a powerless man in the face of a great unquestionable force.

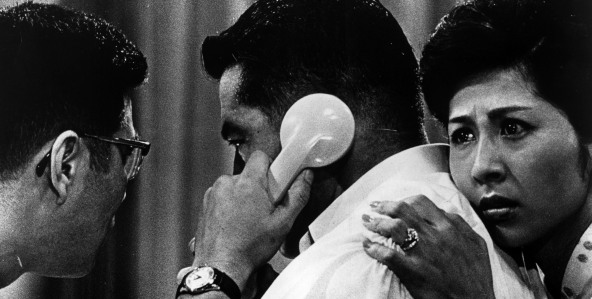

19. High and Low - (1963, Dir. Akira Kurosawa)

My favourite from the famed Japanese director. The 'high' and 'low' has a number of connotations here; the social unrest between the rich and the poor, the spatial distance between kidnapper and Mifone's astonishing Kingo Gondo, it is even a crude reference to the drug idled underbelly to which the film moves towards in the final act. What starts as a terrifically tense Hitchcockian domestic thriller about a kidnapping gives way to a thorough and extended police procedural drama with reactionary commentary towards the emerging social commentary, few films make tire pattern analysis this entertaining.

My favourite from the famed Japanese director. The 'high' and 'low' has a number of connotations here; the social unrest between the rich and the poor, the spatial distance between kidnapper and Mifone's astonishing Kingo Gondo, it is even a crude reference to the drug idled underbelly to which the film moves towards in the final act. What starts as a terrifically tense Hitchcockian domestic thriller about a kidnapping gives way to a thorough and extended police procedural drama with reactionary commentary towards the emerging social commentary, few films make tire pattern analysis this entertaining.18. There Was A Father - (1942, Dir. Yasijuro Ozu)

A delicate film about a father's sacrifice to ensure the future of his son is one of Ozu's quietest, and best dramas. Regular Chishu Ryu is wonderful as the tender and caring father, that distances himself from his boy after a tragic accident at the school he works. This film is simple, honest and elegant perhaps more so than most of Ozu's work. It is because of its release date, that There Was a Father becomes distinctly political, I doubt it was much to Ozu's intent but it looks to place the film in history.

Few other directors carve such intense sensuality from the human form as Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-Wai and In The Mood for Love is a film made of candle lit delicacy. Love unsoiled by love. The two neighbours, who bond over their partners infidelity gradually develop a captured passion for each other. Every shot, movement and hair is composed to such a measured perfection. It toys with us, excites us and eventually burns through us. When it's over, we have to turn to any hole we can find, whisper our emotions and then cover it up.

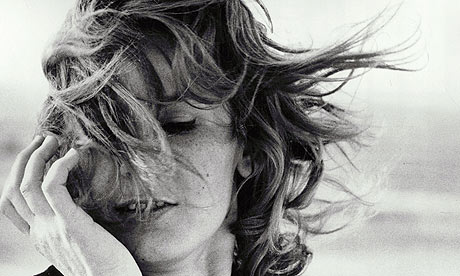

16. Shame - (1968, Dir. Ingmar Bergman)

If Bergman had anything that resembled an action film, this would be it, even including a tense getaway as the couple (Sydow and Ullman) drive through an ongoing invisible battle. It isn't a look at what war turns us into that makes Shame one of the Swedish master's greatest films, it is the effect it has on a couple's relationship. Both actors give some of their finest work, but it is Ullman who delivers one of the most devastating lines in cinema history and the final, apocalyptic image shakes you down to your very core.

15. The Apartment - (1960, Dir. Billy Wilder)

Along with Psycho, Billy Wilder's morally grey comedy about a man who lends his apartment out to his bosses so they can conduct their numerous affairs represents the breakdown of the Hayes code. Jack Lemon's C.C. Baxter represents the increasing deterioration of American ideals. An every man, having to exploit the decrepit nature of those above in order to succeed. The beautiful, desirable Miss Kubelik played by Shirley MacLaine is another victim of such nature, one who has been beaten one too many times and attempts a harrowing suicide. Wilder see's too it he gets the laughs, the chemistry between Lemon and MacLaine is terrific, and his script is, as usual directly acute. But rarely does mainstream American entertainment come with such a grey scale moral compass.

The first in Bergman's faith trilogy is one of his most harrowing films, he looks at the strain of mental illness on a family. Bergman fractures himself and his relationships between the four characters. The Spider-God's presence looms over the family, driving them to destruction. It is one of the most tangible and devastating images in Bergman's complete cannon. Yet there is a singular bead of hope in the film's final line 'Father spoke to me.'

13. Barry Lyndon - (1975, Dir. Stanley Kubrick)

Kubrick's detached coolness that dominated (most) of his films in full force here, literally to the point where the narrator tells us the events before they happen. Ebert raises an interesting point; this can work as a companion piece to 2001: A Space Odyssey as a piece about survival and evolution. One on a mass scale, one a selfish and essentially minor one. Although here I don't find any ethereal alien gods guiding Barry. Instead there is a sense that he makes his own fate, even if he is unaware of it. Kubrick utilizes pretty much every tool at his disposal to tell his story of insignificance. Deep and shallow focus, trade mark tracking shots, candle light, wide angle landscapes, zoom outs and ins, close ups, repeated classical music motifs and of course, the detached narrator. It's a picturesque feast.

12. Pierrot le Fou - (1965, Dir. Jean-Luc Goddard)

Goddard's explosion of pop art and colour has been my favourite journey into the French New Wave and one of the most gloriously entertaining films I've had this year. A married man runs off with his babysitter in a (often violently) clashing satire on society. It's the cinematic equivalent of throwing everything the wall and seeing what sticks. The result is, well, most of it.

11. Two-Lane Blacktop - (1971, Dir. Monte Hellman)

This was probably the purest, most profoundly cinematic road movie of them all. Not only is one of the most interesting preservation of 70s, it's the definitive counter culture piece. The sparse use of dialogue is made all the more effective by how fantastic the subtle interactions are between the cast. At once a love letter to the connection between man and car, a dissection of isolation and an examination of the pro-masculine, American obsession of drag racing.

10. Pale Flower - (1964, Dir. Masahiro Shinoda)

A more mature entry in the Yakuza genre in response to Suzuki's surreal madness. A sultry look at the life and path of a Yakuza from a man on the cusp of middle aged. Pale Flower is a darker jewel of Japanese New Wave, gorgeously shot and featuring a dryly sensual score by Toru Takemitsu. Ryô Ikebe's performance is one of weight and experience, but it is in the darkly beautiful face of youth belonging Mariko Kaga that his disillusionment is transfixed leading him back into the labyrinth that is the criminal underworld.

9. Kiss Me Deadly - (1955, Dir. Robert Aldrich)

The final noir, Aldrich pushes every element of the genre towards destruction. Our hero is a primal brute of pure chauvinism, our femme fetale is broken and spread across five women, who's combined efforts amount to nothing. Then of course it is a case of the secret at the bottom of the box, the great whatzit. It is of course, nothing, nothing but destruction. A blinding burning hiss of white light that burns through the frame, consuming all in the cinematic space itself. Kiss Me Deadly drives the short lived genre, in its purest form, into the nuclear pit where it collides with other forms and cultures emerging a self-aware hybrid, led by that unearthly scorching hiss.

8. The Passion of Joan of Arc - (1928, Dir. Carl Dreyer)

A film of pure visual emotion. Falconetti's performance is truly one of the greatest in the whole medium. Every element is driven by expression, by unsuppressed emotion. The sparse sets reduce everything to its most human and wholesome. The jurors loom over Joan, physically dwarfing her. Just looking at Falconetti's face is a draining and devastating experience, her eyes become a window, unflinchingly looking deep into the human soul. You literally see a woman bare her all in the face of a manipulative and cruel system. The newly released Masters of Cinema Blu Ray, a contender for best Blu Ray of the year, offers it as it should be seen, in complete silence.

7. La Jetee - (1962, Dir. Chris Marker)

Poet, philosopher and artist Chris Marker ponders the relationship between images, memory and time, in this radical science fiction film. It follows a survivor of a devastating world being thrust back and forth through time in order to ensure the survival of the human race. Through his journey he finds immortality, it is located within a museum filled with stuffed animals, a stripped of their essence. Composed almost entirely of still photographs, it punctuated by a single awakening moment of film. That is the moment of pure, unmatched clarity, the returned gaze of the person you love.

6. The Leopard - (1963, Dir. Luchino Visconti)

The ballroom dance that the film's final act is structured on is not only a triumph of art direction, set design and cinematography, it is the swan song of two era. Burt Lancaster's (who gives one of the finest performances ever) Prince Salina is part of a class long gone, a leopard replaced by a hyena, but the film is also part of a bygone era. Sculpted so extravagantly and paced with complete grace, it represents a by gone era of film makers and making. Seldom does film making reach such a grandiose scale.

5. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927, Dir. F W Murnau)

If L'Atalante was a haunting look at loves spontaneity, Murnau's Sunrise is a fever dream. A virtually uncompromising explosion of love, coming from the darkest place. Our young couple impassioned with each other, blaze through a city just as impassioned with their love. For just a few hours, we give our complete selves to these nameless lovers and every problem in the world melts away with them. 85 years old, it is graciously immortalized by it's complete earnestness.

4. Sansho The Bailiff (1954, Dir. Keji Mizoguchi)

The delicacy of human life is tested to the extreme in Mizoguchi's masterpiece. Although firmly Eastern in its setting and style, it's story is in line with Greek tragedy. The story of a family torn apart by evil is one of the most human and eye opening films apart. Some truly devastating moments, when the family is separated it is marked by unsympathetic music, highlighting the hopelessness. Even still Anju's sacrifice might just be the most perfectly composed moment in this list. The final empathetic image has a degree of hope, the human spirit remains tested but in tact in Mizoguchi's brutal world.

3. Bigger than Life - (1956, Dir. Nicholas Ray)

Nicholas Ray's operatic masterpiece breaks down and reverses many of the nuclear family ideals, James Mason plays Ed Avery, a middle class school teacher who is given cortisone to suppress his the development of a fatal illness. Treatment becomes dependency, and it is not long before dependency becomes addiction, turning Avery into an egotistical maniac and something much more disturbing. Brilliantly shot on CinemaScope, Ray's impassioned domestic monster movie is perhaps the best film in the directors vibrant, passionate canon.

2. Harakiri - (1962, Dir. Masaki Kobayashi)

Just as Kiss Me Deadly is brought a nuclear destruction to the noir genre, Harakiri is the anti-samurai film tinged with apocalyptic hatred. Kobayashi see's no glory or honor, only death here. A man with nothing left to lose tries desperately to expose a corrupt and evil system. Long corridors represent a Kafka-labyrinth of bureaucracy. The bold chiaroscuro cinematography crash through each frame with devastating clarity, the film opens with a shot of empty armor, a monument to the facade of this empty system. As his last action, Hanshiro Tsugumo tears it down. Yet as, Harakiri ends with the armor rebuilt, the disruption off record and system intact. But its effect lingers long after. Brutally fierce, cruel and emotionally draining. It is a masterpiece of blood, sword and snow.

1. The Decalogue - (1988-89, Dir. Krzysztof Kieslowski

Kiewslowski's monumental cinematic movement made up of ten short films based on the Catholic interpretations of the ten commandments is, quite possibly the art form's greatest achievement. While some entries are flawed in their own right, as whole the series transcends cinema, even art. Although religious in subject, it is not in nature. Kieslowski searches for the spiritual and finds only suggestions. Each entry is shot by a different cinematographer, each character is therefore allowed their own visual perspective of the world, one such example would be the intense grime in entry V (which would become A Short Film About Killing.) Yet they are linked through music and visual motifs such as milk or the ever present 'watcher.' Kieslowski creates a micro-universe and fills it with everything that we, as a race have. Thus, The Decalogue becomes a work of profound humanism, intimately capturing every moment in the fabric of our existence. From prodigious actions of some to the minute connections between strangers, through the apartment block the series is set we experience immense pain and disgust to unwavering love and miraculous joy. It ends with the single most human image ever committed to film, the image of laughter.

It was, undoubtedly, the best film(s) I had the pleasure of viewing this year and I'll be damned if it is topped for some time.

[Honorable Mentions: Youth of the Beast, Tokyo Drifter, The Naked Kiss, Stalker, Belle et le Bete, Repulsion, Wings of Desire, Robinson Cruesoe on Mars, No End, Camera Buff, Cries and Whispers, Sans Soliel, If.., Lost Weekend, Walkabout, The Ballad of Narayama, Modern Times, The Royal Tenenbaums, Close-Up, Amarcord, Red Dessert, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie]

So that does it, 2012 has been one continuous eye opening cinematic journey for me, one that I cannot wait to continue in the year to come. Happy New Year everyone!

No comments:

Post a Comment